The digital clock tells all who are present that it is 11:11. From what I know through comments hither and yon is, that 11:11 sticks in the minds of many. It is symbolic, I suspect. It is for me. Of course, on a digital clock the symmetry of the display catches one’s eye and captures a little bit of imagination. 11:11. A digital clock cannot duplicate this with other numbers, certainly. Unless is it a twenty-four-hour clock. Eleven hours and eleven minutes later it would read, 22:22. I don’t think I’ve ever seen a twenty-four-hour digital clock. I’m sure they exist. I’ve just not seen one.

This is all to say, when I see 11:11 on a digital clock I think of George Stratton. Every time without fail. George and I began to notice the number configuration at eleven minutes after eleven o’clock. The dials would roll around and line up on all ones and either of us, if we noticed, would grunt or say something like, “Thar she blows”. 11:11 equals George Stratton. George and I were shipmates on one of the first nuclear submarines, USS Sam Houston. We were part of the commissioning crew. It was 1960 when rapid advances in electronics were changing the fabric of technology. New words and phrases were flooding the lexicon of electronics and physics and other science-based fields. People who had graduated college with EE’s were crawling over and under equipment throughout the fleet. We technicians were learning along with the rest of the world about things that only geeks previously cared about.

Radar and sonar were old hat. Navigation by measuring radio wave lengths and triangulation was old news. Regardless of how we thought of radio wave detection, sound wave detection, and Loran navigation links, these were all rapidly being overrun by the technology brought by space-oriented systems that were hundreds of times more accurate and way more reliable. We still hadn’t perfected satellite positioning. That would come in another five years.

Gyros and accelerometers were carrying the day. Orthogonality became a major part of our discussion. Gravity. Not just simple gravity but gravity that represented a pull toward the center of the earth for the location specific. Gravity pulls slightly off vertical in places. Spherical triangles came into our consciousness. We needed to understand what spinning weights and balanced wheels bathed in oil were able to do for us. 1’s and 0’s were talking to us now. Magnetic memory encased in aluminum cabinets packed in static cores or spread around spinning drums solved complexities way faster than our customary slide rules and hand-held calculators. In a few months we old-boat submariners took on the cutting edge of inertial navigation. We would be able to accurately plot our position on the earth’s surface completely submerged while out of touch with humanity. Our technology was depending more on digital rather than analog information. Dials with tiny graduated marks and numbers were being displace by the glowing nixie-tube number behind the glass doors of computers. It was “Buck Rogers”!!! We were living so far into the future our mouths were perpetually agape. Industrial designers must have been working 24/7 to produce the machines, cabinets, displays, binnacles and other un-imagined systems for navigation. Incidentally, Buck Rogers was a comic strip first published in 1928, thirty-one years before my first peek inside a nuclear submarine. As I write this, the date is fifty-nine years later. Buck Rogers was equivalent to all of the space adventurers today; Han Solo, Luke. Leia, Obi-Wan, Rae, and Finn. We even wore one-piece Polaris Patrol suits while on patrol. It didn’t take long for the nuclear submarine crews to bastardize the “Polaris Patrol” to “Poopy Suits”. We stayed under the surface of the wide oceans for months without surfacing. We morphed into space-men within a few years. Heady stuff for knuckle-dragging boat sailors.

We truly were transitioned, from unbathed, smelly, diesel and hydraulic oil-soaked humans to showered and foo-foo’d, combed and trimmed space travelers. We were still submariners. Side note here: Submariner is pronounced thus, from Wikipedia. This word is generally pronounced like sub- + mariner (for example, in the U.K. Royal Navy and the U.S. Navy); however, since the prefix sub- was apparently deemed to imply inferiority (as in subpar or subhuman) rather than the actual meaning of “under,” this pronunciation may be considered offensive by non-submariners. The pronunciation submarine + -er, but with stress on third syllable, is preferred by Naval Brass. As evidence of submariners’ collective lack of concern for the opinion of non-submariners on any matter, many submariners refer to themselves by the much more negative terms of “sewer-pipe” sailor, or “bubble-head.” Submariners often refer to sailors that work on the surface of the ocean as “skimmers” or “targets.”

There is a much larger issue related to George Stratton from my recollections. George and I had a relationship that was rare for most men. We got each other. Often, we could share information with a glance. The amount of eye-contact upon meeting and during a few hours in each other’s company was filled with meaning. A smirk, a shake of a crossed foot, a tap of a pencil would punctuate the look; give it additional weight. He would say something non-verbally and then I would lean onto the chart table and grin. That was all it took to transmit a phrase. This followed with a chuckle and a grinding out of a cigarette (in those days) would fill in the blanks and assign priority or weight or immediacy. We liked each other and later in our lives, when we spoke on the telephone, I noticed George had taken on a persona which included the use of words that indicated he’d become a man of faith. His sentences were punctuated with “Lordie” or “Good Lord”. He was agreeable to a great degree. Not like younger George who was cynical and saw the dark side of life with no great difficulty. Young George was solid, aware, caustic with those who wouldn’t learn or try to be part of the fabric of our society. He detested Barry Goldwater. Goldwater’s run for the presidency had made up a slogan, “In you heart you know he’s right!” George altered that to, “In you guts you know he’s nuts!”

I would call George when he lived in California long after I was retired from the Navy. He was happy to hear my voice, as I was his. Without eye to eye contact though we needed more words to communicate. He sounded old. No fire. No zip. He was happy though. He was married and comfortable with what was going on around him. I think he had children. I can’t recall. We last spoke some years ago. He had cancer and not long to live from what he told me. He was limited to what he could do or where and how far he could go. It wasn’t the same. Still we could share details without fear of being misunderstood. I think we comforted each other naturally.

During those underwater, deterrent patrols George would occasionally break out in poetry. My favorite was his recital of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”. He would adjust his position on the seat in front of the Navigation Control Console. That would involve his straightening up a bit and fishing a cigarette out of his breast pocket. A quick flip of his Zippo and a few puffs to get the smoke going, he’d look toward the overhead of our watch center and blow the smoke and with a twinkle in his eye he’d intone, “’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves, Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:, All mimsy were the borogoves, And the mome raths outgrabe.”… at which point he’d look in my direction and grin as he continued on and on through the whole darn thing. I was always impressed that he could remember all that stuff.

George and I made six patrols together. Each patrol lasted for three months in which the first month was spent alongside the submarine tender in Holy Loch, Scotland. The first month was used to make regularly scheduled maintenance for all equipment. Many of the items needed to be put out of commission in order to perform upkeep. Therefore, the submarine stayed in port during this period. At the end of the first month all was ready to test. Usually we would leave port and go on what is called a sea-trial, which is about 2 days or so. Upon returning to port after a successful trial, the crew would be fully engaged in loading parts and stores for the two-month patrol. By this time, we all were exhausted and ready to leave port. Going to sea was the beginning of long days but the long days included regular rest periods and plenty of down time to catch up on sleep and regular meals. It was during one particular upkeep period when a personnel storm showed itself on the horizon.

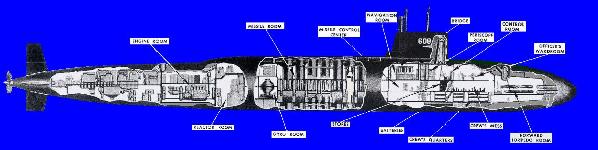

In the early years of assigning watch standers and repair technicians to the newly formed crews of the submarines, like Sam Houston, there were changes necessary to adjust numbers of watch-standers as well as assigning responsibilities for operation vis-à-vis maintenance tasks. Typically, operation of various items is simpler than maintenance. Any sailor can be trained to turn on and properly use the item as long as the machine is in proper working condition. The technicians perform endless checks and tuning and communicating with the operators to effect good maintenance practices. In the case of the equipment in the Navigation Center of the submarine there was no school or training regimen to teach the initial assignment of Quartermasters to be skilled watch-standers. The equipment was too complex and difficult for them operate. The Electronics Technicians were the best choice to operate the navigation computers and plotters and be fluent in the “Buck Rogers” terminology. The problem with the decision to use the technicians for this task was, in the early 60’s, there were only 6 Electronics Technicians assigned to the submarine who were trained to maintain all of these computers, plotters, star tracking periscope, multi-speed ship’s repeaters, navigation aids, inertial navigation gimbals, and the ancillary equipment that supported the operation and maintenance of the whole shebang. Oh, by the way, there were logs to be kept and reams of printed out paper that needed to be annotated and stored for after-patrol analysis ashore. Six men. That is how we ended up. The Electronics Technicians took on the task of operating and maintaining all of the equipment in the Navigation Center.

The Navigation Center was the part of the ICBM Polaris System that provided the missiles with position data up to the point of missile launch in order for the missile to find the target over a thousand miles away. We needed to be precise. It took a lot of work to perform this job. Especially in those early years when we were going to sea with brand new concepts that required hours, days of repairs/alterations to get the whole system working perfectly. We six men were overloaded. That’s the story of how important it was for each of the six men to be healthy and trained and able to do the job.

Our watch-standing routine in the Navigation Center was typically three sections, four hours on and eight hours off. Four hours of watch-standing is plenty as the required focus and precision is demanding. The tension can get quite high. It takes a lot of attention-to-detail as well as a keen sense of what is happening with each piece of equipment to determine all is right. The cooling fans make specific noises that one gets used to, the steady glow of panel lights that indicate phases of operation are usually fixed in patterns that assist the operator in the quick-glance check for normalcy. A slight shift in cooling fan speed was enough to make a good watch stander sit up straight and become alert to a failure about to happen. So much goes on when there are fourteen main-frame computer cabinets and three gyro binnacles as well as a time standard and a tape punch all going at once. There were two men each standing three section watches. Our six men were busy.

The storm brewing on the horizon was this. Herbie (last name not important) had received a phone call from his wife Cherry. Herbie’s mother had died. They were not particularly close. Hadn’t been for years. She lived in the south-central part of the U.S. She left Herbie the farm plus $15,000. This is in the early 60’s, remember. He got the phone call in the beginning of our upkeep month. We’d just recently arrived in Holy Loch and things had just begun to settle into a routine. Herbie suddenly was rich. He decided to seek a way to get out of going to sea with us. He cooked up a scheme with Cherry. It involved an age-old story of trust, or lack of. Herbie and Cherry made up a fiction of infidelity on her part that worried Herbie and caused him to be worried about leaving her home while he was going away for three months. That is the story they invented.

The trouble with their plan was that Herbie and Cherry were good friends with me and my wife. I knew their marriage was good. I also knew Herbie was capable of lying. Hell, we all are. When I found out that Herbie had been visiting the Chaplain on the Tender along-side I quickly figured he was gaming. I smelled a rat and it didn’t go down well with me. Herbie was eager to leave us short handed for the sake of getting out of the Navy on some sort of trumped up humanitarian discharge. I wasn’t going for it.

The first opportunity I had I called Herbie on his scheme. He wouldn’t acknowledge my inquiry. That upset me more. We needed more than six men to do the job we were tasked with. We could have used three men on watch instead of the two we had and here Herbie was making one of our watch sections short-handed. We would need to go into two section watches of six on and six off to cover our duties adequately. I told Herbie that I was not going to let him screw the crew over this way. I told him he was full of shit to tell the Chaplain that Cherry was cheating on him. I told him that the cat was out of the bag, that we were all aware he’d come into some money and that he was gaming the system to get out of the Navy. Nuh-uh. No way.

I reported the situation to the Navigator, Lieutenant Commander Bill Usilton. He looked into it some more to verify what I was accusing Herbie of. He consulted the Chaplain on the tender and our Ship’s Doctor. It all checked out. Herbie was gaming the system. Usilton came to me a few days before we were to leave port on patrol. He asked me if I wanted to leave Herbie in port or take him along. I told him there was no way that I would let Herbie pull this shit on the gang. I told Usilton that Herbie had to go with us to stand watches. I would take Herbie into my watch section so I could keep an eye on him. Usilton went along with my decision. “O.K.”, he said and that was that. By now Herbie was not talking to anyone in our gang. He was really pissed at me for holding him aboard.

I need to take a side-bar here and put all this into perspective. All of us, the six of us, were around twenty-five years old. Pretty much still youths in regard to character development. We were physically in our prime. Psychologically was another story. Plus, this was in the early sixties. We were children of the forties and fifties. I hope this explains the culture in which this story takes place. If I had to do this in the present with what I have learned during the past fifty-five years I would have let Herbie go do his thing. I’d recommend he be taken off the submarine and dealt with by the Navy. Hindsight is twenty-twenty.

I was the senior petty-officer of the six-man Navigation Center crew. It was my job to run the show. I made up the watch sections and supervised the operation and maintenance of the complete Navigation Center. My title was “leading petty-officer”.

I placed Herbie on watch with me. I pulled him aside and instructed him that I wasn’t going to put up with any bullshit from him. That he was to do nothing in the Navigation Center unless he told me first. He was to stay away from me at all times but stay within my line of sight. He needed to stay aft but where I could see him. He was not to leave without my permission. If he wanted to do something while on watch with me, he needed to approach me in a normal manner and tell me what it was he wanted to communicate. Herbie remained reticent during these instructions. He maintained eye contact, held his hands in his pockets of his poopy suit and nodded when it was appropriate. When I was through speaking, I told him to take station in the aft end of the Navigation Center. This is how we stood watches for the next two months.

I am not proud of how I treated Herbie. We had developed a distrust of each other and our friendship disintegrated to nothing. The tension built slowly throughout the patrol. After our four-hour watch we would go to separate parts of the boat. We avoided any contact outside of the Navigation Center. Herbie had some friends in the sonar gang where he spent some time off-watch. After our eight hour off-watch time we would reconvene our silent standoff in the Navigation Center. Herbie would approach me a few times per watch and inform me he needed to go to the head or he wanted to get coffee and did I want one? I let him bring me a cup of coffee one time. He delivered it to me while I was busy taking data from the Navigation Control Console. He approached with two cups of coffee. I took mine black with nothing in it. He had two cups; mine was in a very dirty cup with stains running down the sides of it. I took the cup, sipped out of it and thanked him politely. With full on eye contact. My look said, “Fuck you” and his return look said, “Same to you”.

This is how we spent the remainder of the patrol. That is until two weeks before we were scheduled to surface. Herbie had begun to decompensate. He was more and more unkempt. His eye contact came less. He kept his hands jammed into fists deep into the pockets of his poopy suit. It was obvious that he was in trouble. At this point in time. George Stratton had begun coming back the Navigation Center after he’d eaten his meal. George would return and quietly sit in the Type 11 periscope booth behind me while I was at the Navigation Control Console. He would mention the food or who he’d bumped into in the mess hall. A little gossip and then we were quiet with occasional comments about how the patrol had gone so far. George did this for each watch. He’d come back and sit with me. Herbie remained at the aft end of the Navigation Center. About 3 days of this, twice a day George returning to sit with me, I saw that George had a 12” crescent wrench in his back pocket. George caught me looking at it and he just sat more silently and still and watched my expression. I looked at George. His look said it all. George told me in zero words but in one brief glance that he was standing watch over me. George had friends in the sonar gang too. He’d heard that Herbie was up to no good or at least he’d heard enough to know that Herbie had become dangerous. George was coming back on watch with me until he was certain that Herbie was not going to cause mayhem.

George died peacefully a few years ago. He was gentle and at ease with his cancer. I will always remember George at 11:11. When I see 11:11 I never fail to say, “Hi, George Stratton”. What a shipmate.

The ship’s doctor was informed that Herbie was getting more and more radical in his behavior. With the assistance of the corpsman the doc injected Herbie with a sedative and kept him under control for the remainder of the patrol. I was on watch alone but a couple of my other technicians took turns coming to the Navigation Center to make sure I was o.k. and to relieve me for head breaks and coffee runs.

After we returned to port Herbie was written up and found to be competent enough to return to sea. This time he was transferred to an oiler headed for the Mediterranean Sea for six months. He left two weeks after we returned to New London. I ran into Cherry down at the Groton Mall a few months after our patrol. She took a detour to avoid speaking to me. I never ever had an experience like this again. Herbie and Cherry, what a pair. I don’t know.

G. M. Goodwin

8 February 2019